The scene in the Gospel is pretty straightforward. John encountered an outsider who exorcised in the name of Jesus. Undoubtedly, there was bewilderment. Can the power of Jesus be possessed by an “outsider”? The reaction could be a jealous attempt to curb the outsider from what he had been doing.

The answer Jesus gave: “Those not against us are for us” is surely music to the ears of those who stand for the spirit of openness, diversity and acceptance1 as suggested by the theme which stresses how God’s Spirit can work outside “boundaries”. Today, the Gospel invites us to reflect on the meaning of belonging to Christ.

For those who do not subscribe to an “inclusive, pluralist and politically-correct” ideology, to speak of “belonging” is to venture where angels fear to tread. An attempt to insist on strict membership would be deemed as parochial or provincial or in some cases, downright uncharitable—certainly out of touch with the spirit of openness and tolerance. It would appear that Christ and exclusion do not belong together.

However, consider the perception that the Orthodox Churches are numbered amongst some of the fastest growing religious organisations in the United States.2 These Churches are unabashedly resistant to the tides of relevance.3 Correspondingly, the mainline Protestant churches, suffer a significantly higher number of losses, wracked as they have been by contentious issues on sexuality and ordination.

Caught in the churning currents of constant change, people seem to seek the secure shores of stability. Similarly with the present credit crunch in the Eurozone raging there is a yearning for the familiarity of the old regime—a case of better the devil you know than the devil you do not know. What we are witnessing is none other than a enervating backlash of the tyranny of relevance which is manifested by a certain listlessness, a debilitating ennui that has compelled people to search for security and they seem to find it in Churches with the most solid past. The Orthodox Churches seem to represent that.4

The phenomenon of the rise in membership articulates a primæval urge to belong. Belonging has always been a sociological given. We say, “No man is an island”. In times gone by, we never seemed to question it. We just belong. Whether we subscribe to the set of values proposed by our belonging, we simply belong more or less.

Today that cannot be assumed. Whether it be religious persuasions or philosophical convictions, our shared worldview has retreated behind the walls of private belief or opinion.5When that happens, our grasp of the bigger picture that is provided by religious belief or philosophical framework is now transferred to the narrow field of ideology. In our experience it is called “social justice”. Do not think that I am knocking “social justice”. No, the truth is, since we cannot be certain that our religious content is real or that our philosophical framework can be universalised and all we are certain of is that the world is a mess, so, we attempt at a world morality.6 As a result of this breakdown in shared beliefs or assumptions which provide belonging together sociologically, what happens is that the urge for belonging must be expressed somehow or rather.7

Our locals have a colloquial saying, “shiok sendiri”. It is derived from the English word “shock” (as in the experience of being jolted by electricity). Literal translation renders this saying as self-satisfaction. Left to our own devices, we search for ways to entertain ourselves. Because belonging is near to impossibility, we resort to entertaining ourselves. It sounds absolutely miserable because we run from reality TV to adrenalin rushes, to mindless car crashes in movies all in the hope that the “shiok” will certainly satisfy the “sendiri”.8

If dancing around the pole of pleasure does not lead to the satisfaction of the urge of belonging, then the question has to be asked of the John’s insistence of membership: “What is the purpose of membership”?

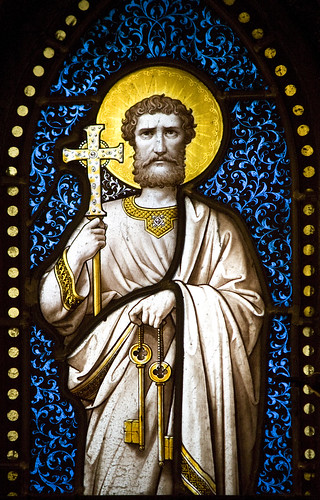

If an innate or inbuilt sociological urge to belong does not really answer our question of membership, then we are force to venture further into the deeper sea of existence to ask the question of Truth. Membership in the Church misses the point if the membership does not revolve around the question of Truth. We are in for the Truth. And that is why Church membership is important because Truth is our salvation.

Here, there is no assumption that the other religions do not search for Truth. In fact, they do and if they do, a further question to be asked is: Where is Truth to be found in its fullest? This is a question which a broken down world dares not ask. In fact, the Gospel of Nice prevents us from asking this question because it is afraid of the implication of Truth; that there is really a line between black and white and that there is the possibility of exclusion.9 Instead of upsetting people by making truth claims, let us remain at the mundane level of attempting to build heaven here on earth.10

The sense of belonging that the Disciple wanted was rightly so corrected by Christ because in practical sense, we do not start out on life with the assumption that everyone who is not with us is against us. We do not need to because there are people who believe but they do not belong. For example, two religions share the same belief that life is sacred and yet one religion is not the other. Hence, the sense of belonging that the Disciple desired must go deeper. It revolves around a belonging in Truth.11

In summary, we can believe without belonging. The world is made up of many who believe without belonging.12 However, to belong without believing is impossible. And this is our challenge as baptised individuals. Our belonging or our membership in the Catholic Church is not just to fulfil a sociological urging. It is more fundamental for in the Church, we are fundamentally united in Truth, that is, Christ, so that we may live Him to the fullest. If we do not want to be condemned to a life of endless twirling around the pole of pleasure, with our minds numbed by the array of self-seeking shiok-sendiri entertainment13, then we must ask this question: “What is the purpose of my belong to the Church.”?

1 This is the same kind of mind-set at work in a question like “Why Holy Communion cannot be given to Protestants since we are all followers of Christ”?2 Here, I am touching only on Christianity. It should be noted too that Islam is a fast growing religion.3 A good example is how we approach the Eucharist. Catholics consider their Eucharist to be valid because they fulfil the requirement of having a valid Order. So, we are allowed to receive Holy Communion in their Churches, if a Catholic Church is not readily available. They, on the other hand, are not always open to us receiving Holy Communion from them because they consider us as heretics. Thus, they would, in general, resolutely resist receiving Holy Communion in a Catholic Church.4 The Catholic Church may draw people to her bosom. But, the fact is that those who go for the Orthodox Churches would put as a reason the seeming wishy washiness of Catholic theologians.5 Except for the so-called dictatorship of relativism—which imposes its particular brand of “tolerance” etc.6 Whilst you are here, you house may be burglarised. When you get stopped by the Police, you are certain that the Police be asking you for “coffee money”. The world is very messy.7 Today more than ever, belonging is not assumed but it is a personal choice. Judging by how we often keep to ourselves, we can say that many have opted out of society. They are happy or content to enjoy the benefits of society minus the convictions, implications and most of all the responsibility of being a part of that society.8 Have you come across game show which attempts to maximise the participant’s excitement even though he is being kicked out. I play Plants vs Zombies, the Survival panel and the rationale for playing is to score as many flags as possible killing zombies and the truth is, it is never satisfying because I keep wanting to get more and more flags. The same is with “Angry Birds”. I will try to achieve 3 stars and when I cannot seem to get that for a particular panel, I inevitably end up in a mindless attempt to perfect the ballistic angle etc etc. In the end, I sin because it becomes a waste of time.9 It is not politically incorrect to speak of “hell” and that people can go there. Otherwise, heaven does not exist.10 Losing sight of the eternal we will be condemned to roam the desert of practicality.11 I have been a Jesuit for 26 years. In my brief work as campus minister and in the short years I have been a parish priest, I have dedicated my ministry to making people, especially the young understand not just the consequences of their actions (admittedly, we falter all the time) but also to become a real community of believers. The only way to save the word (not true in a sense because only Christ saves) is when we become a community of believers. It means we share the same faith and speak the same language and because we share the same faith and speak the same language, the possibility of common action becomes more a reality. The Jesuits think that they speak the same language but scratch the surface of two Jesuits and you will find two different philosophies which may be inherently incompatible with whatever common actions they participate in. In other words, common actions do not denote a shared understanding at all. What might be true is that the two Jesuits might be striving at cross-purposes even though they are both engaged in the common apostolate. This is not easy to hear. Why? Because we gloss over the question of truth of the competing philosophies believing that common actions are enough to unite us. In a sense, the Pope’s Regensburg speech got caught in the dumbing down fog of the Gospel of Nice. In bringing up the example of a violent character, he was not condemning but rather he was asking, “Is it true” that the religion espoused violence. The aftermath reaction may have proven the Pope’s point.12 Mahatma Gandhi is our most famous believer Christ who resolutely refused to be a Christian, for obvious reasons. We scandalise him by our behaviour. “I believe in Christ, I don’t believe in Christians”.13 Just like Odysseus’ chapter 9 where ill winds blew his ship off-course, landing upon an island of lotus-eaters. The men who have tasted the lotus flowers very soon forgot the purpose of their journey which was to get home.